Charter Implications

Except with regard to medical marijuana (discussed below), Canadian courts have not explicitly recognized Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms implications for Canadian psychedelic law. However, case law suggests a right to medical use of and access to psychedelics may exist under the Charter. The question of what constitutes sufficient access, though, so as to comply with the principles of fundamental justice required by the Charter, complicates matters and remains somewhat unclear.

Below we review the case law and explore potential Charter implications for Canadian psychedelic law.

Note: On July 27, 2022, a group of patients suffering from cluster headaches, opioid use disorder, and terminal cancer filed a claim against Canada’s federal government to argue for a constitutional right of access to psilocybin-assisted therapy. The claim is now pending in federal court. We’ve written about the lawsuit in greater detail here.

R. v. Parker (2000)

In Parker, Terry Parker’s counsel successfully argued that convicting him for illegal marijuana possession and cultivation in contravention of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA) would violate his rights under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Parker was a Torontonian who suffered severe epilepsy. His experiences with conventional medicine were only moderately successful in treating his epilepsy. As the Ontario Court of Appeal wrote, he found that by smoking marijuana, he could “substantially reduce the incidence of seizures.”

By criminally prohibiting Parker from accessing a substance required to effectively treat his epilepsy, the court found the law violated his s. 7 rights to both liberty and security of the person.

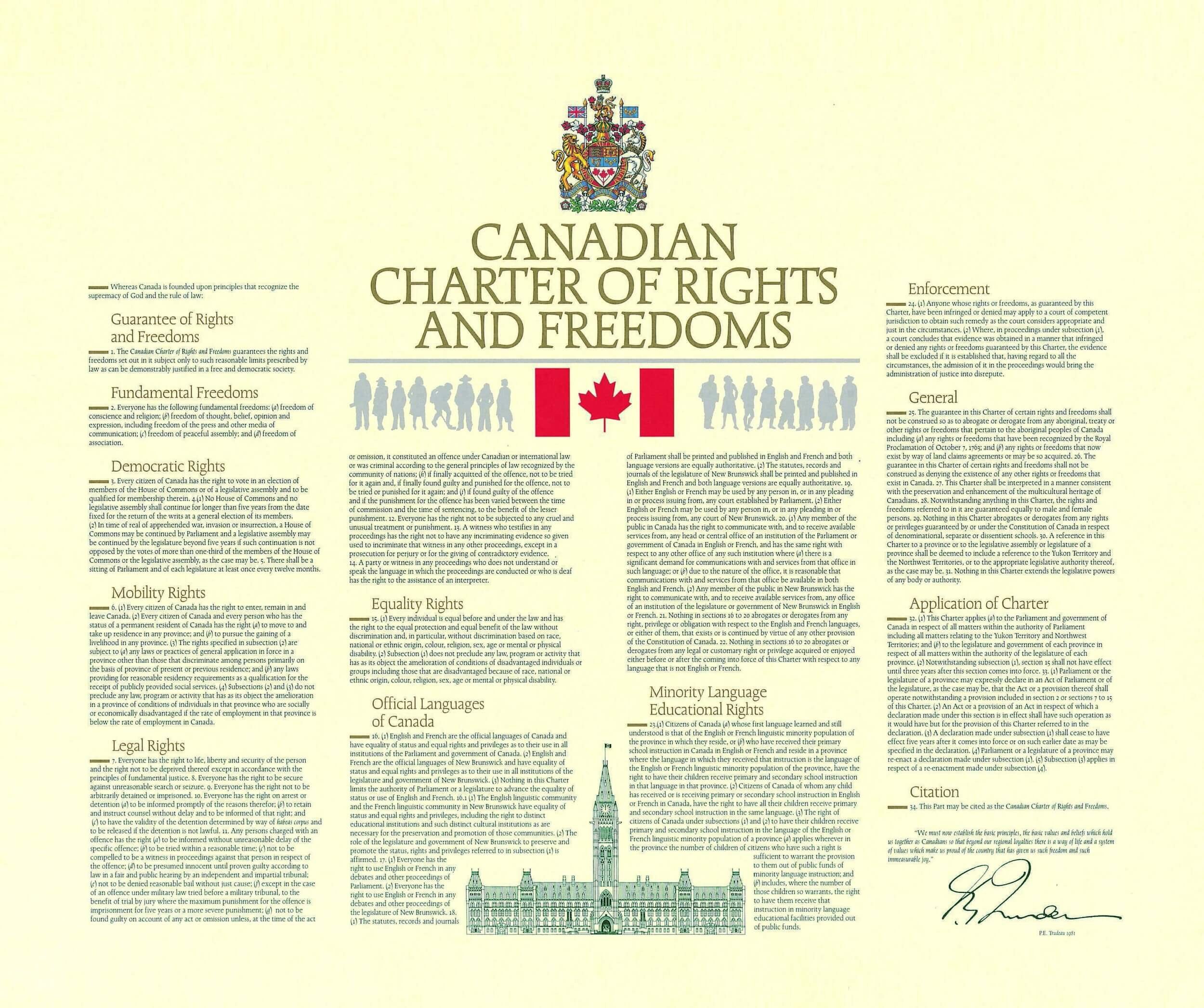

“Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of the person and the right not to be deprived thereof except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice.”

s.7, Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms

The court found that Parker’s s. 7 liberty interest included “the right to make decision of fundamental personal important, including the choice of medication to alleviate the effects of an illness.” The criminal prohibition of medical marijuana violated this interest. Furthermore, the court found that prohibiting Parker “from accessing a treatment by threat of criminal sanction” constituted a violation of his s. 7 right to security of the person.

“[A] broad criminal prohibition that prevents access to necessary medicine is not consistent with fundamental justice.”

Ontario Court of Appeal in R. v. Parker (2000)

Though the government argued that applicable persons could seek a medical exemption to the criminal law under s. 56 of the CDSA, the court found that remedy did not provide adequate access for those seeking to use medical marijuana. Nor did the court find that the government had a sufficient state interest in criminally prohibiting individuals from accessing medical marijuana.

Accordingly, the law was to be struck down. The court gave the federal government one year to establish a Charter-compliant regulatory regime for legal access to medical marijuana.

Canada (AG) v. PHS Community Services Society (2011)

In PHS Community Services Society, the Canadian government, led by Prime Minister Stephen Harper of the Conservative Party, tried to effectively shut down Insite, the first supervised drug injection site in North America, located in Vancouver. The action was challenged in court, and the Supreme Court of Canada determined that the health and safety benefits Insite provided were of such consequence that forcing its closure would violate the Charter rights of those using it as a safety injection site.

Insite, which opened in 2003, had been operating by means of a s. 56 exemption under the CDSA. The exemption was extended in 2006 and 2007. In 2008, the Minister did not extend the exemption, meaning the site would no longer be able to legally operate. In response, the Vancouver charity non-profit organization PHS Community Services Society (which oversaw Insite’s operation), the Attorney General of British Columbia, and several other interested parties sued the federal government. They argued, among other things, that the CDSA violated Insite clients’ s. 7 Charter rights to life, liberty, and security of the person.

“In order to make use of the lifesaving and health‑protecting services offered at Insite, clients must be allowed to be in possession of drugs on the premises. Prohibiting possession at large engages drug users’ liberty interests; prohibiting possession at Insite engages their rights to life and to security of the person.”

Supreme Court of Canada in Canada (AG) v. PHS Community Services Society (2011)

In discussing the CDSA and s. 7 of the Charter, the Supreme Court of Canada looked favourably on the law and its design. As the court wrote, “[T]he CDSA confers on the Minister the power to grant exemptions…on the basis…of health...If one were to set out…a law that combats drug abuse while respecting Charter rights, one might well adopt just this type of scheme — a prohibition combined with the power to grant exemptions.”

“If there is a Charter problem, it lies not in the statute but in the Minister’s exercise of the power the statute gives him to grant appropriate exemptions.”

Supreme Court of Canada in Canada (AG) v. PHS Community Services Society (2011)

The court found that the CDSA did not violate Insite patients’ Charter rights, but that the government’s refusal to extend Insite’s s. 56 exemption to operate did. It ordered the government to renew Insite’s exemption.

Insite remains operational to this day.

Is There a Canadian Charter Right to Psychedelics?

The precedent created by Parker and PHS Community Services Society suggests that when a person’s (or group of persons’) health and safety may substantially benefit from access to a substance in a medical context, s. 7 of the Charter prohibits the government from preventing access to that substance. Where Parker and PHS Community Services Society diverge, however, is on the question of sufficient access.

In Parker, the Ontario Court of Appeal ruled that in the context of obtaining necessary medication, permitting access solely by means of s. 56 exemptions was unacceptable. A more flexible and accessible regulatory scheme was required. In the case of PHS Community Services Society though, the Supreme Court of Canada found that permitting possession of a prohibited substance in an appropriate medical context solely by means of a s. 56 exemption was acceptable - but refusal to grant that exemption where appropriate was unacceptable. As PHS Community Services Society was decided by the Supreme Court of Canada, whereas Parker was decided by the Ontario Court of Appeal, PHS Community Services Society is the controlling precedent.

However, distinctions can be drawn in that in PHS Community Services Society, the party applying for the exemption was Insite, a facility with the resources to go through the complicated s. 56 exemption process. By contrast, in Parker, Terry Parker was an individual for whom jumping through the regulatory hurdles would be more difficult.

Applying this lens to psychedelics, one can imagine courts finding that where an individual seeks medical access to psychedelics, requiring them to go through the s. 56 exemption process will not constitute sufficient access, per the ruling in Parker. And then, in the case of institutional entities providing patients with access to psychedelics, denying them an exemption may constitute a Charter violation per the ruling in PHS Community Services Society, if the exemption request is denied without sufficient justification.

This also suggests the possibility of a compromise system emerging by which the government exempts institutional entities providing supervised medical access to psychedelics, and in turn, individuals seeking medical psychedelics can access them through those institutions. In this scenario, the government may not be required to establish a regulatory regime for individual access to psychedelics if the courts find the system provides sufficient access to satisfy Charter principles.

January 2022 Update: Recent amendments to Special Access Program regulations may weaken the calculus behind a Charter challenge with respect to medical psychedelic access. The new regulations allow health practitioners in Canada to submit individual request to Health Canada for patients contending with serious or life threatening conditions to access psychedelic therapy.

This appears to be a big step forward from requiring a s. 56 exemption from the Minister of Health in terms of increasing accessibility. However, the practical effects of the regulatory amendment have yet to become apparent. If Health Canada appears to be overly restrictive in granting requests, that could give rise to new legal challenges per the PHS case described above.